The eighth episode of Cosmos, “Journeys in Space and Time,” returns to the style of earlier episodes with a specific topical focus: space and time (rather obviously). It’s an information-heavy installment that takes place for the most part in Tuscany, where both Leonardo Da Vinci and a young Albert Einstein did their intellectual work. The episode begins by discussing the constellations again and uses that as a springboard to discuss issues of distance, perception, and the speed of light—all considering the stars and our relationship to them. Sagan illustrates the connections between space and time by diving into a discussion of travel to the stars and the problems posed by the general theory of relativity (time dilation, etc); that leads into a set of thought experiments on time travel and speed-of-light travel. It’s also, as might be clear by now, one of the more science-fiction-friendly episodes.

The return to the informative, topic-driven style is a definite shift from the last several episodes, which have focused on big ideas. “Journeys in Space and Time” reminds me much more closely of the opening episodes of the series—its primary purpose is to deliver factual information and offer explanations of contemporary phenomena related to its subject. As such, it’s a more sedate episode than the past two, which dipped their proverbial toes into turbulent waters regarding religion and science among other contentious issues. This time around, the sharpest line is an aside about the only good use for nuclear weapons—though it’s a very good aside.

“We are drifting in a great ocean of space and time. In that ocean, the events that shape the future are working themselves out. […] The roots of the present lie buried in the past.”

Whether we realize it or not, we are always already time and space travelers. That’s the singular idea that sticks out to me in this episode—our tendency to remain unaware of the nature of our motion on the surface of the Earth on a daily basis, or our shifting through time from moment to moment. But, they’re happening regardless. It’s a thought that I find at once sobering and fascinating. The “always already” thing applies to a lot of aspects of postmodern life, but we don’t often apply it to scientific paradigms; in this case, I think it’s something good to keep in mind. Even the most wild speculation—travel to the stars, travel through time—is already happening in mild and innocuous forms in our every-day life.

It’s sort of like looking at a smartphone and actually thinking about the computing power I’m holding in the palm of my hand. Pretty big deal, and yet we notice it hardly at all.

Of course, it’s not only one line from the opener that I find neat in “Journeys in Space and Time.” Sagan, throughout the episode, illustrates the constancy of space/time as well as how we’ve come to understand their functions as natural laws via a series of thought experiments. The thought experiments themselves, and the visual effects the episode uses to work through them, are particularly memorable—and also make the occasionally complex information more easily understandable. Visual effects, thought experiments, and speculation form the core of this episode, fleshing out the theory of general relativity that stands as the main data-point. I find them all memorable and informative.

One of my favorites is actually early in the episode: the bit where Sagan shows us, using a computer simulation, how the constellations looked far in the past and how they might appear far in the future. It’s a brief throwback to the astrology episode, but digs in much more deeply to the problems of vantage point and perception than that episode did—I love the attention paid to the various different contemporary constellations, and how each will change/has changed in a different way. Comparing the expansion of the “big dipper” into a strange, long line in the past to the future of Orion is thrilling. The birth and death of bright, hot stars within the area of Orion over millions of years is just stunning—and the way it’s represented on screen is effective, though remarkably simple, just dots of color moving on a dark background. Though we all know, now, that the stars move and that we move in relation to the stars, seeing how that change works—something we weren’t alive during and will be dead long before—is something that I won’t forget. It’s the ultimate speculation: what will the sky look like to the beings on earth in a few million years? And it’s accurately computed, too.

Those stars and their movements lead to a discussion of how we receive their light, and a few simple but evocative lines: “We see that space and time are intertwined. We cannot look out into space without looking back into time.” To look at a star, we see that star as it was seventy-five years ago, a hundred years ago, or billions of years ago—before our galaxy even formed. That’s sort of the theme of this episode, really, the way I see it: simple but overwhelming truths. The scope is almost unreal, and that’s no different now than it was in 1980 or a century ago, or further back still.

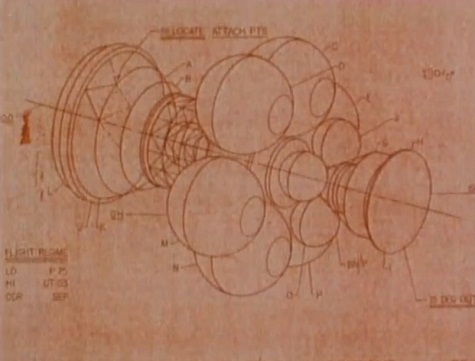

And how could we get there, to those stars? Of course science fiction readers are familiar with just about every proposal for travel near the speed of light, or travel to the stars without it—generation ships, nuclear fusion engines, ships with scoops to power their travel, etc. The illustrations of these potential ships, as Sagan discusses them, are nostalgic and a bit dated; all the same, it’s a provocative section of the episode, because of the comparison to Da Vinci. His flying machines may not have worked, but he still started the ball rolling on the process. Which leads us, also, into time travel, and one of the best zingers of the episode: what if we could take out a major figure in the past as a time traveler—like, say, Pythagoras?

As we noted in the last episode, Sagan is not a fan of Pythagoras. His not-so-subtle suggestion that the world would have been a vastly better place without the suppression of science Pythagoreans enacted is as amusing as it is disheartening. Superstition and greed have, certainly, set us back—with that I don’t disagree. And maybe, if we could time travel, it’d be good to create a timeline without Pythagoras. (But not in the hideous “time machine” from this episode. Good lord.)

The one last thing I found intrigued by this episode is Sagan’s explanation of why we do thought experiments at all—because, “The universe is not required to be in perfect harmony with human ambition.” So, we can’t actually travel at light speed. But we can think about what it would mean, and what the effects would be, those familiar problems like aging slowly and coming home to dead friends and relatives, or if you’ve gone far enough, a dead planet. It’s a subtle thumbs-up for speculation, one that the “Update” about Sagan’s own novel seems to support, and it’s worth remembering.

*

Come back next week for episode 9, “The Lives of the Stars.”

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.